Cybersecurity researchers have revealed a cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerability in the web-based control panel used by StealC operators—an information‑stealing malware. The flaw allowed investigators to gather valuable intelligence about one of the actors deploying the malware in real-world campaigns.

“By taking advantage of the bug, we were able to capture system fingerprints, observe active sessions, and—ironically—steal cookies from the same infrastructure designed to steal them,” CyberArk researcher Ari Novick explained in a report released last week.

StealC first appeared in January 2023 as part of a malware‑as‑a‑service (MaaS) offering. Its operators made heavy use of YouTube, a distribution technique known as the YouTube Ghost Network, by disguising the malware as cracked versions of popular software.

Throughout the past year, additional infection vectors have been observed, including fake Blender Foundation files and a social engineering technique known as FileFix. During this period, StealC itself has evolved, adding features such as Telegram bot notifications, improved payload delivery, and a redesigned command‑and‑control panel. The updated release is referred to as StealC V2.

Soon after, the source code for the malware’s admin panel leaked online, giving researchers an opportunity to study the tool closely. This enabled them to gather indicators from threat actors’ systems—including approximate location details, hardware characteristics, and active session cookies extracted from their own devices.

The specific technical details of the XSS flaw have not been released, as disclosing them could allow the developers to patch the issue or enable copycats to abuse the leaked panel to launch their own MaaS operations.

Generally, XSS vulnerabilities are client-side injection attacks where malicious JavaScript executes in the victim’s browser when a vulnerable site loads. Such flaws typically stem from improper validation and encoding of user input, and can allow an attacker to steal cookies, impersonate users, and access sensitive data.

“Considering StealC’s entire business revolves around stealing cookies, you might expect its developers to at least secure their own cookies using basic protections like httpOnly,” Novick said. “The irony is that an operation built on large-scale cookie theft failed to secure its own session cookies against a classic attack.”

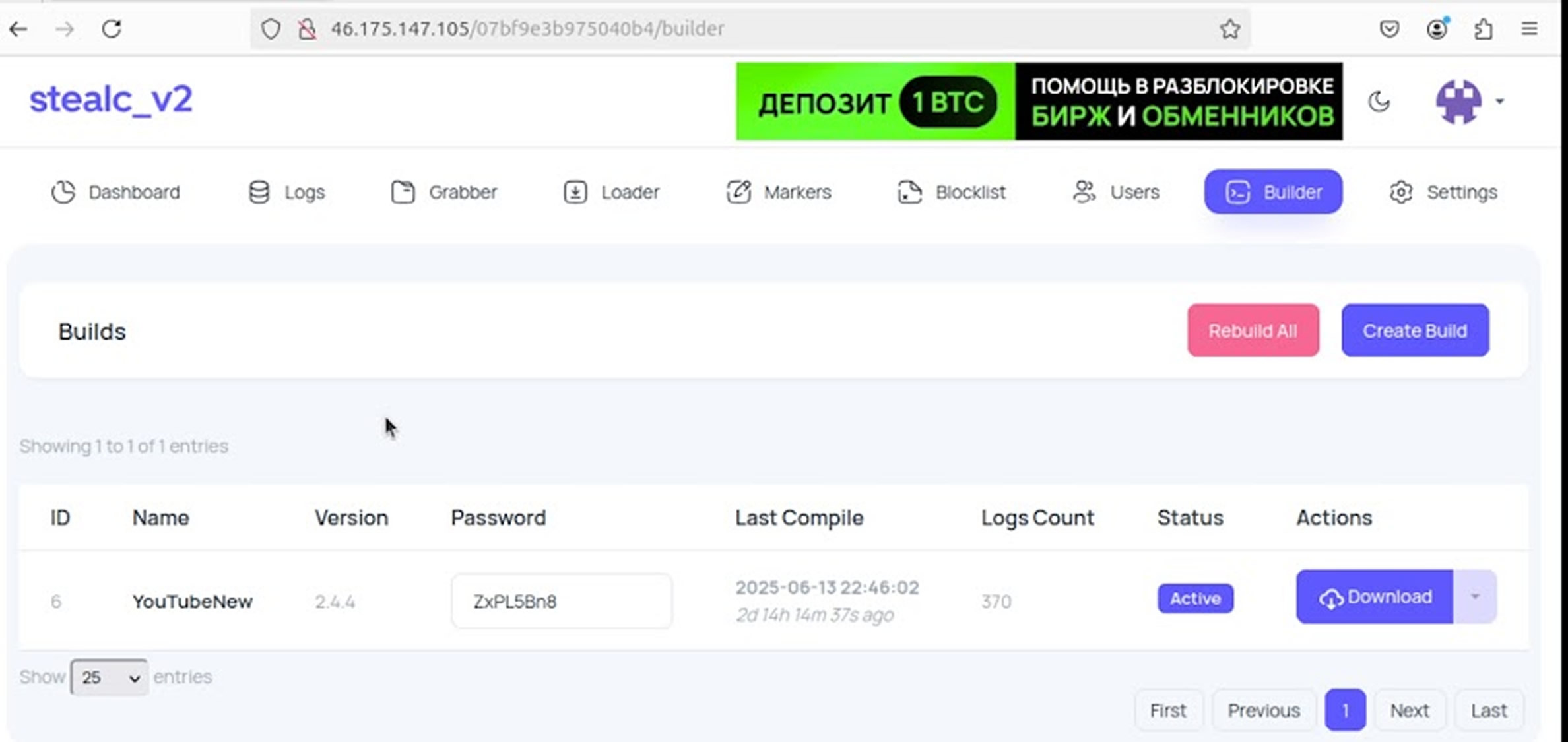

CyberArk also profiled a StealC customer known as YouTubeTA (“YouTube Threat Actor”). This individual has heavily relied on YouTube to spread the malware by promoting cracked versions of Adobe Photoshop and Adobe After Effects. Their campaigns generated more than 5,000 logs containing 390,000 stolen passwords and over 30 million stolen cookies—most of which were tracking or otherwise non‑sensitive.

Researchers suspect these tactics helped the actor compromise legitimate YouTube accounts and use them to further promote pirated software, creating a self‑reinforcing distribution loop. Evidence also suggests they employed ClickFix-style fake CAPTCHA lures to deploy StealC, indicating their operations extend beyond YouTube-based infections.

Further investigation into the panel showed it supports multiple user accounts with distinctions between admin and standard roles. In YouTubeTA’s case, only one admin account existed, associated with a machine running an Apple M3 processor and configured with both English and Russian language settings.

In a significant operational security oversight, the threat actor accidentally accessed the StealC panel without a VPN around mid‑July 2025. This exposed their real IP address, which was linked to a Ukrainian provider named TRK Cable TV. The evidence suggests YouTubeTA is a lone actor operating from an Eastern European region where Russian is commonly spoken.

The research highlights how the MaaS ecosystem enables threat actors to scale quickly, but also exposes them to many of the same security weaknesses that affect legitimate software developers.

“The StealC developers demonstrated weaknesses in cookie security and overall panel code quality, giving us the ability to gather extensive information about their customers,” CyberArk noted. “If similar flaws exist in other malware offerings, researchers and law enforcement may be able to use them to gain insight into—and potentially identify—the operators behind various malware campaigns.”

Found this article interesting? Follow us on X(Twitter) ,Threads and FaceBook to read more exclusive content we post.